Vasovagal syncope interrupting sleep

CT Paul Krediet, David L Jardine‡, Pietro Cortelli§, AGR Visman || and Wouter Wieling*; * Department of Internal Medicine, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam (The Netherlands); ‡ Department of General Medicine, Christchurch Hospital, Christchurch (New Zealand); § Neurological Section, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Bologna (Italy); ||Department of Cardiology, Beatrix Ziekenhuis, Gorinchem (The Netherlands)

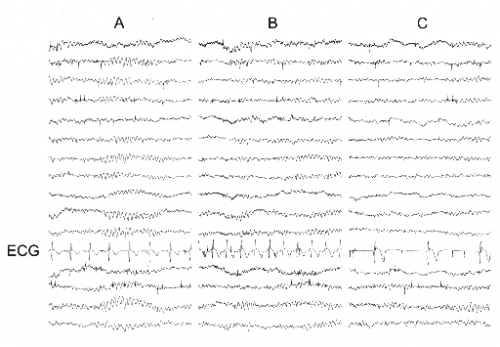

Panel A: time 5:49 AM, normal sleep EEG, heart rate 90 bpm.

Panel B: time 5:50 AM, EEG unchanged, heart rate 126 bpm.

Panel C: time 5:52 AM (after calling for nurse), patient lying supine in bed unable to move, EEG unchanged, heart rate 36 bpm. Patient is pale and sweating profusely.

A female patient had her first nocturnal syncopal episode at the age of 40. She woke up at night after sleeping for some hours, aware of nausea, abdominal discomfort and an urge to defecate. She lost consciousness while supine. She sweated profusely but did not bite her tongue. Her husband observed transient myoclonic jerking. After this, similar episodes occurred regularly (at least one per month) and only at night. The syncopal episodes never exceeded one minute and were atraumatic. She was incontinent of urine and faeces once. A tilt test provoked a vasovagal reaction followed by 7 seconds of asystole and reproduced her nocturnal symptoms. Because of ongoing symptoms she underwent neurological investigations and a typical nocturnal episode was recorded during permanent EEG and ECG monitoring.

The EEG was judged normal by two independent neurologists. The ECG however showed a pronounced bradycardia (36 bpm) during the episode, with an atrioventricular node escape rhythm. At the age of 44 a permanent dual chamber pacemaker was implanted and the patient reported less syncope but ongoing episodes of nocturnal pre-syncope with abdominal discomfort [1].

Editor's comments

At three syncope units world-wide we saw 13 patients (10 females) with nocturnal episodes similar to patient A . They all gave a history of waking up at night with nausea and urge to defecate. In some patients syncope occurred in bed; in others immediately after leaving the bed in an effort to get to the toilet. The syncope was of short duration and often accompanied by profuse sweating. After regaining consciousness most patients felt very weak and could not remain upright but were orientated. Bradycardia was documented in 5 patients. The frequency of attacks varied from weekly to annually and there was no relation to menstruation or alcohol. Three patients reported nightmares immediately before the episode. Some patients had learned to partially abort the episodes by remaining supine in bed. Nine patients also had daytime syncopal and pre-syncopal episodes associated with vasovagal symptoms.

Tilt table testing was performed in 11 patients and was positive in 7 with typical prodromal symptoms. A significant (asystole >3s) cardio-inhibitory reaction was recorded in 4 of the 7. The possibility of organic cardiac or cerebral pathology causing as a cause for the episodes was excluded by appropriate additional testing. Interictal EEG performed in 7 patients revealed epileptiform activity in one.

We concluded that the patient in this report, as all of the patients mentioned above have nocturnal vasovagal syncope as the primary cause of their symptoms. Although the attacks start when the patient is supine, the associated symptoms described are typical of vasovagal syncope. These include: nausea, sweating, light headedness, abdominal discomfort and weakness during the attack, followed by tiredness afterwards. Because the attacks occur at night in bed, epilepsy is often diagnosed especially if muscle jerking is observed. However it should be realized that transient myoclonic jerking is more often a feature of cerebral hypoperfusion than epilepsy (see Case about EEG). Other more reliable features of epilepsy including tongue biting, post ictal confusion and hypersomnolence are absent. Based on an algorithm derived from a recent study on historical criteria that distinguish syncope from seizures [2], all of our patients fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for vasovagal syncope with very high levels of certainty (>90%). Furthermore, we have demonstrated a normal EEG during a typical nocturnal episode in one patient and normal inter-ictal EEG’s in 46% of the group.

The association with nightmares is suggestive of a central trigger similar to the mechanism proposed for vasovagal syncope associated with phobias. Syncope is occasionally triggered by bowel evacuation or colonoscopy, and has been induced reliably by inflating rectal balloons. Thus the predominance of pronounced gastrointestinal symptoms associated with these attacks would suggest a gastro-intestinal trigger mechanism. Because there was no association with the consumption of spicy food or alcohol, nor were there any symptoms of gastro-enteritis we think that abdominal discomfort is more likely to be an effect of vagal over-activity rather than the cause. The prominent cardio-inhibitory response during tilt table testing suggests a cardiovascular autonomic imbalance which may also occur during sleep.

Based on our observations, we think that patients who have nocturnal loss of consciousness and classical vasovagal prodromal symptoms should be considered to have true vasovagal syncope. A positive tilt table test can support this diagnosis, as the test`s sensitivity is low. Long QT and Brugada syndromes should be excluded by ECG. Also mastocytosis should sometimes be excluded.

Patients with nocturnal vasovagal syncope should not be treated with anti-epileptics. If long term ambulant ECG-monitoring shows pronounced bradycardia or asystole, a pacemaker may improve symptoms. However, because vasovagal syncope is believed to be a relatively benign condition, patients should initially be reassured and be given an explanation of the known, however so-far poorly understood pathophysiology.

References

<biblio>

- Krediet This case was earlier published in: Krediet CT, Jardine DL, Cortelli P, Visman AG, Wieling W. Vasovagal syncope interrupting sleep. Heart 90: e25. We thank the BMJ Publishing Group for permitting this reproduction.

- Sheldon pmid=12103268

<biblio>