Hypotension due to straining in a patient with a high spinal cord lesion: Difference between revisions

m (April moved page Psychological treatment of malignant vasovagal syncope due to bloodphobia to Hypotension due to straining in a patient with a high spinal cord lesion: Duplicate page. Reusing page for a new one.) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'' | ''J.J. van Lieshout, W. Wieling''<br /> | ||

'' | ''Department of Medicine, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam (The Netherlands)''<br /><br /> | ||

{{case_present| | {{case_present| | ||

A | A 44 year-old woman was admitted because of complaints of dizziness (lightheadedness) related to singing, debating and car parking [1]. As these complaints were not related to orthostatic stress her complaints were initially judged as psychoneurotic. She was known with an incomplete spinal cord lesion (CV-CVI) since the age of 17 due to a motorcycle accident, with partial residual function of the hands. Notwithstanding her physical disability she had given birth to twins and had a job as a doctor's assistant. She was a singer in a steel band. In association with the spinal cord lesion she had related symptoms such as automatic (reflex) bladder, spasms, recurrent urinary tract infections with stone foration, obstipation and occasional orthostatic dizziness. | ||

[[File:SpinalCordLesion_Fig1.jpg | thumb | left | 300px | Figure1. Cardiovascular responses to singing (left) and head-up tilt (right). On singing a scale blood pressure drops sharply at high pitched notes; this is comparable to the circulatory effects of about 10 mmHg of Valsalva straining (see Figure 2).]] | |||

On physical examination a dissociated sensory loss from level CV-ThI was found with a paralysis from ThI and paresis of the forearm flexors, loss of triceps tendon reflexes bilaterally, an extensor plantar reflex and variable muscle tone with leg spasms. On NMR scanning narrowing of the cervical spinal canal at CII-CV (VI) was established with a medullary lesion at CVI-VII which was confirmed by somatosensory evoked potentials. | |||

Supine blood pressure was low (80/40 mmHg) with normal plasma catecholamines (noradrenaline 170-295 ng/l, adrenaline 25-40 ng/l) and elevated plasma renin activity (PRA 4.0 ng/ml). Upon sitting in a wheelchair for 20 min blood pressure fell slightly (-8/-2 mmHg) without changes in catecholamine level (noradrenaline 155-235 ng/l, adrenaline 25-35 ng/l) and with a small rise in PRA to 4.8 ng/ml. Provocation of symptoms by singing showed that both systolic and diastolic blood pressure dropped markedly within a few seconds till near-fainting (Fig. 1). On graded 45o head-up tilt heart rate increased from 72 beats/min (bpm) to 100 bpm with a slight systolic blood pressure drop (80/40 to 70/45 mmHg); on additional tilting up to 70o blood pressure and heart rate did not change (Fig. 1). | |||

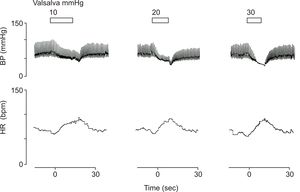

[[File: | [[File:SpinalCordLesion_Fig2.jpg | thumb | 300px | right | Figure 2. Blood pressure responses to graded straining. Pulse pressure during Valsalva phase II drops progressively without recovery; its magnitude is proportional to the Valsalva strain.]] | ||

A drop in blood pressure comparable in magnitude and time course could be reproduced by a low strain Valsalva manoeuvre (10 mmHg). Small increments in the Valsalva straining pressure induced a rapid progressive fall in pulse pressure during the strain to a state of disappearance of the pulsatile blood pressure signal (Fig. 2) indicating absence of arterial blood flow. On echocardiography during a 30 mmHg Valsalva strain the left heart chamber emptied almost completely. | |||

During head up tilt BP gradually diminished with an inversely related increase in heart rate. These differential effects of orthostasis and strain were reproducible [1]. | |||

}} | |||

== Editor's comments == | == Editor's comments == | ||

In patients with a high spinal cord lesion arterial pressure is usually low, depending on the amount of residual spinal cord reflex activity. Although sympathetic outflow has become isolated from control by the brain, orthostatic tolerance is usually reasonably maintained; as in our patient tetraplegics tend to endure the upright posture in a wheelchair with minimal symptoms much of the day [2-4]. | |||

Circulatory adaptation to orthostatic stress in these patients is attributed to activation of spinal sympathetic reflexes acting through the isolated spinal cord [2], to local veno-arteriolar axon reflexes [4,5] and to activation of the renin-angiotensin system [2,3]. The small renin release in the sitting position in this patient is in accordance with the minimal postural fall in blood pressure [3]. | |||

We found a peculiar contrast between relative normal orthostatic tolerance and severe complaints of dizziness induced by singing, debating and car parking. We documented that the dramatic effects of a moderate strain on blood pressure, as involved in daily life physical exercises, accounted for this contrast. By provocative manoeuvres like singing a drop in blood pressure was observed comparable in magnitude and time course to the response to a low (10 mmHg) strain Valsalva manoeuvre. | |||

In healthy subjects the Valsalva manoeuvre comprises a voluntary elevation of intrathoracic and intra-abdominal pressures resulting in a displacement of blood from the thorax to the limbs but not to the abdominal cavity [6]. Patients with high spinal cord lesions lack control over their abdominal muscles and rely on the clavicular part of the pectoralis major muscle to blow against a high counter pressure [7]. Their ability to strain is less but the effects on the circulation appear larger; we attributed this to pooling in the abdominal cavity because of failing of compression by the abdominal wall muscles and loss of control of splanchnic venoconstriction. The expected fall in cardiac filling volume could indeed be visualised in our patient by echocardiography. The finding of a relation between the small stepwise increments in strain pressure and the fall in pulse pressure during the Valsalva manoeuvre supports our view that mechanical circulatory effects are responsible for the observed paradox of relatively normal orthostasis and debilitating hypotension on straining. | |||

Hyperventilation and straining are important predisposing factors in syncope [8]. During hypocapnea cerebral blood flow is markedly decreased at all perfusion pressures. Changes in cerebral blood flow induced by pCO2 changes are normal in spinal man [9] and a decrease in PCO2 comparable to the level in our patient (PCO2 kPA) would halve cerebral blood flow [10]. The effects of chronic hypocapnea on arterial cerebral blood flow are unknown; nevertheless it might have contributed to deterioration of an already compromised cerebral blood flow in our patient. In addition hypocapnea induces systemic vasodilatation. Treatment with a high salt diet and bicarbonate improved her clinical situation and, together with explanation of the mechanism, was sufficient to prevent further syncope or near-syncope. | |||

This study shows that ill-defined complaints in these patients deserve a full physiological examination. | |||

| Line 37: | Line 36: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<biblio> | <biblio> | ||

# | #Wieling pmid=15310717 | ||

<biblio> | <biblio> | ||

Revision as of 13:59, 15 July 2014

J.J. van Lieshout, W. Wieling

Department of Medicine, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam (The Netherlands)

A 44 year-old woman was admitted because of complaints of dizziness (lightheadedness) related to singing, debating and car parking [1]. As these complaints were not related to orthostatic stress her complaints were initially judged as psychoneurotic. She was known with an incomplete spinal cord lesion (CV-CVI) since the age of 17 due to a motorcycle accident, with partial residual function of the hands. Notwithstanding her physical disability she had given birth to twins and had a job as a doctor's assistant. She was a singer in a steel band. In association with the spinal cord lesion she had related symptoms such as automatic (reflex) bladder, spasms, recurrent urinary tract infections with stone foration, obstipation and occasional orthostatic dizziness.

On physical examination a dissociated sensory loss from level CV-ThI was found with a paralysis from ThI and paresis of the forearm flexors, loss of triceps tendon reflexes bilaterally, an extensor plantar reflex and variable muscle tone with leg spasms. On NMR scanning narrowing of the cervical spinal canal at CII-CV (VI) was established with a medullary lesion at CVI-VII which was confirmed by somatosensory evoked potentials. Supine blood pressure was low (80/40 mmHg) with normal plasma catecholamines (noradrenaline 170-295 ng/l, adrenaline 25-40 ng/l) and elevated plasma renin activity (PRA 4.0 ng/ml). Upon sitting in a wheelchair for 20 min blood pressure fell slightly (-8/-2 mmHg) without changes in catecholamine level (noradrenaline 155-235 ng/l, adrenaline 25-35 ng/l) and with a small rise in PRA to 4.8 ng/ml. Provocation of symptoms by singing showed that both systolic and diastolic blood pressure dropped markedly within a few seconds till near-fainting (Fig. 1). On graded 45o head-up tilt heart rate increased from 72 beats/min (bpm) to 100 bpm with a slight systolic blood pressure drop (80/40 to 70/45 mmHg); on additional tilting up to 70o blood pressure and heart rate did not change (Fig. 1).

A drop in blood pressure comparable in magnitude and time course could be reproduced by a low strain Valsalva manoeuvre (10 mmHg). Small increments in the Valsalva straining pressure induced a rapid progressive fall in pulse pressure during the strain to a state of disappearance of the pulsatile blood pressure signal (Fig. 2) indicating absence of arterial blood flow. On echocardiography during a 30 mmHg Valsalva strain the left heart chamber emptied almost completely.

During head up tilt BP gradually diminished with an inversely related increase in heart rate. These differential effects of orthostasis and strain were reproducible [1].

Editor's comments

In patients with a high spinal cord lesion arterial pressure is usually low, depending on the amount of residual spinal cord reflex activity. Although sympathetic outflow has become isolated from control by the brain, orthostatic tolerance is usually reasonably maintained; as in our patient tetraplegics tend to endure the upright posture in a wheelchair with minimal symptoms much of the day [2-4].

Circulatory adaptation to orthostatic stress in these patients is attributed to activation of spinal sympathetic reflexes acting through the isolated spinal cord [2], to local veno-arteriolar axon reflexes [4,5] and to activation of the renin-angiotensin system [2,3]. The small renin release in the sitting position in this patient is in accordance with the minimal postural fall in blood pressure [3]. We found a peculiar contrast between relative normal orthostatic tolerance and severe complaints of dizziness induced by singing, debating and car parking. We documented that the dramatic effects of a moderate strain on blood pressure, as involved in daily life physical exercises, accounted for this contrast. By provocative manoeuvres like singing a drop in blood pressure was observed comparable in magnitude and time course to the response to a low (10 mmHg) strain Valsalva manoeuvre.

In healthy subjects the Valsalva manoeuvre comprises a voluntary elevation of intrathoracic and intra-abdominal pressures resulting in a displacement of blood from the thorax to the limbs but not to the abdominal cavity [6]. Patients with high spinal cord lesions lack control over their abdominal muscles and rely on the clavicular part of the pectoralis major muscle to blow against a high counter pressure [7]. Their ability to strain is less but the effects on the circulation appear larger; we attributed this to pooling in the abdominal cavity because of failing of compression by the abdominal wall muscles and loss of control of splanchnic venoconstriction. The expected fall in cardiac filling volume could indeed be visualised in our patient by echocardiography. The finding of a relation between the small stepwise increments in strain pressure and the fall in pulse pressure during the Valsalva manoeuvre supports our view that mechanical circulatory effects are responsible for the observed paradox of relatively normal orthostasis and debilitating hypotension on straining.

Hyperventilation and straining are important predisposing factors in syncope [8]. During hypocapnea cerebral blood flow is markedly decreased at all perfusion pressures. Changes in cerebral blood flow induced by pCO2 changes are normal in spinal man [9] and a decrease in PCO2 comparable to the level in our patient (PCO2 kPA) would halve cerebral blood flow [10]. The effects of chronic hypocapnea on arterial cerebral blood flow are unknown; nevertheless it might have contributed to deterioration of an already compromised cerebral blood flow in our patient. In addition hypocapnea induces systemic vasodilatation. Treatment with a high salt diet and bicarbonate improved her clinical situation and, together with explanation of the mechanism, was sufficient to prevent further syncope or near-syncope.

This study shows that ill-defined complaints in these patients deserve a full physiological examination.

References

<biblio>

- Wieling pmid=15310717

<biblio>